Learning Forward Resources: Engaging the Leader and the Learner

Some good advice from a colleague and friend.

It’s pretty amazing that one of the most powerful tools you have as a leader is something you’ve been doing since you first started talking. By now, you’re probably good at it, it doesn’t cost a thing, and you can start using it more effectively by the time you finish reading this article: asking questions.

Asking questions is essential for building empathy, understanding, and trust — all of which are necessary for group success but are sorely lacking in today’s divided political climate. In a time of immense stress among and unusual hostility toward educators, listening and learning are among leaders’ most important responsibilities. And asking good questions is a leader’s superpower.

As I once heard education author Phillip Schlechty say, it’s not the leader’s role to have the answer to every question. It is the leader’s role to be sure that all the right questions get asked and answered. I would add that it is also the leader’s role to listen to a variety of perspectives and consider a wide range of suggested answers.

That sounds easier than it is. Look around at contentious school board meetings, angry social media posts, and staff meetings driven by an administrator’s long to-do list. How often are we really trying to understand one another? How curious and interested are we in those whose opinions differ from our own? Now look at the results. We haven’t been very successful in bridging our divides.

Fortunately, you can greatly elevate your listening skills — and your overall effectiveness as a leader — by simply being more intentional about how and when you ask questions. Here are six ways to do that. They can be useful to leaders of all levels and at all times — not just when there’s a conflict or a global crisis.

1. Recognize that asking questions of others builds your own knowledge.

If you or I think we bring more individually to a given problem, plan, or decision than our team does collectively, one of two things is probably true: either we’re dangerously delusional or we have an historically weak team — and the former is much more likely to be true.

I very rarely know more about a given subject than the combined wisdom of all of the people around me. Learning from them is an efficient way to broaden my knowledge of whatever the task is we’re working on because each of them has specific technical knowledge related to their primary responsibilities that I don’t have, and they also have a wealth of practical experience that can inform our decisions.

To tap team members’ vast trove of knowledge and experience, ask questions like:

- Who among us has had personal experience with an issue like this?

- Are you aware of another organization that has navigated this issue, and what can we learn from them?

- Who else can inform our decision?

- Are there differences in how various demographic, religious, and political groups in our organization/community will see this issue?

- Is there history in the community/organization that will be an important factor in the context in which we’re working?

2. Create an open, safe space for people to respond honestly and insightfully to your questions.

Looking for a surefire way to avoid hearing alternative perspectives to your own? Start a team discussion with a lengthy, passionate exposition of your current thinking and your probable position, and then ask your team members what they think. You might get some head nods, but you probably won’t hear any new ideas.

As leaders, when we start with our own conclusions, we’re basically putting team members in a position to either agree or disagree. Some may feel secure enough to disagree, but others will not. Instead of sharing what they really think, people will probably hold their ideas and discuss them in conversations after the meeting — and you won’t be invited to them.

How much easier and more productive it is to lead by simply asking the questions that will draw out the best, most relevant thinking of your team members. Those questions include:

- What values should drive our decision?

- What is at stake as a result of this decision?

- What are the potential courses of action, and what are the pros and cons of each one?

- What stakeholder groups will be affected by this decision, and what are likely to be their biggest concerns?

It’s important to note that how we react to team members’ responses is as important as how we ask the questions. It’s critical that we value all responses as the team works through an issue. This can be especially difficult when you and some (or all) of your colleagues start out with very different opinions. But it’s worth the effort.

You’ll not only be getting your team’s best thinking and advice, you’ll also be establishing your expectations of how they’ll lead their own teams. To that end, make sure to set clear norms for discussions and encourage your team members to use them with those they lead.

3. Involve others in the process of formulating and asking questions.

As leaders, we may have a perfectly logical path that we’ve followed to get to a decision. But if we communicate our final answer without taking others through our thought process, our team members may end up feeling uncommitted or even unsupportive of the decision.

Telling them how we got there is better than just announcing that we’ve got the answer, but taking them along on the journey is even better.

One of the best ways to include them on that journey is by engaging them in formulating the questions that need to be asked of the team and inviting them to help find the answers. When you include your team in this process, they’ll be in a position to say, “We asked important questions, looked at a lot of evidence, and listened to diverse viewpoints, and this decision seems to be the best one going forward.” That can make a big difference when those team members in turn share the decision with the people they lead.

An added benefit of this collaborative process is that you’ll be able to anticipate the questions, fears, and conflicting values that the larger community will have as they give input on the decision or react to the decision. Surprises are not a leader’s friend, and they can be minimized by engaging a diverse group to work with you through the analysis and decision-making processes.

4. Communicate that you value your team members as individuals by asking them questions and truly listening.

How does it make you feel when someone asks for your opinion or input? Smart? Informed? Respected as a good thinker? I feel all of that. I believe we assess our worth in the eyes of others with the messages they send about how they see us. And one of the strongest ways we can tell people how we see them is to ask questions and listen to them in ways that tell them we value what they have to say.

If, over time, you ask and truly listen, then those you are leading will start any interaction with you from a basic belief that you value them as a person — even when they disagree with you. That’s a powerful force for eliciting their thinking and ideas and for continuing collaboration.

It’s important to note that an effective and ethical leader doesn’t just ask questions to make people feel valued. That’s manipulation. But if you sincerely want to know what they think and you make it clear that you have heard them and thought about their responses, then they rightly conclude that you value them.

5. Ask questions at the front end of a process so you have the answers when you need them.

With most decisions we make as leaders, there’s a clock ticking in the background. That’s never been truer than today, with virus variants evolving by the day, political firestorms erupting overnight, and urgent social issues pressing on our collective consciousness. It’s helpful to know how much time is on that ticking clock because, as a decision countdown nears zero, there’s less and less time to look into relevant data, research, and other considerations — and if you haven’t gathered the relevant information, you’re more likely to make a poor decision that could have been easily avoided.

Try to anticipate the most relevant information you’re likely to need as you work through an issue or process. By doing so, you’ll have that information ready when it’s needed and avoid scrambling to get it when time is running out. Along the way, additional questions may come up that you didn’t foresee, but they are likely to be few and shouldn’t stall the decision-making process.

Too often, leaders try to collect information as the need arises rather than foreseeing what will be needed and doing that research at the beginning of the process. Consider what happens when you’re painting a room: If you don’t prepare the surfaces, you’ll pay for it later when your paint job comes out patchy and uneven.

Another benefit of this proactive approach to identifying essential research questions is that often the questions can be ordered in a way that suggests a logical path for the decision-making process. In other words, what’s the first thing we need to know? Then what’s next? And so on. This can help you and your team develop an orderly plan for how to proceed.

6. Use questions to enable others to develop themselves as leaders.

One way to measure a leader’s legacy is to take stock of how much they have enabled others to develop themselves as leaders. Note that I didn’t say “how they develop others as leaders.” The distinction is important.

Think of a physical fitness trainer you may have worked with. Was that trainer able to “develop” your physical condition with no effort of your own? Of course not. You were successful to the degree that you learned and applied what the trainer made available to you. I’m with Kouzes and Posner (2006), who, in their book The Leadership Challenge, observed that “ultimately leadership development is self-development.”

Skillful use of questions is one of the most powerful ways leaders can create an environment and opportunities for others to learn and develop themselves — and, at the same time, grow a pool of leadership that will have impact long after you’re around to see its results.

As leader, you might ask questions such as these that challenge others to reflect on their leadership and find their own answers to challenges they face:

- What knowledge and skills do you lack or need to refine to be successful in the challenge you’re facing?

- What resources or individuals can you tap into that will be helpful?

- Whom do you need to recruit as team members and perhaps allies?

- Where do you anticipate support for change?

- Where do you anticipate resistance?

- Who are the key individuals and groups that you’ll need to communicate with early and often?

I see the role of a leader in enabling others to develop themselves as a matter of calibration. My mental image of this calibration is a sound mixing board with knobs or slides for different frequencies or, in this case, leadership behaviors. Just as the sound board operator can adjust various factors to get the right mix for the music, so can you calibrate your work with individuals to lead them in the way that is uniquely tailored for them.

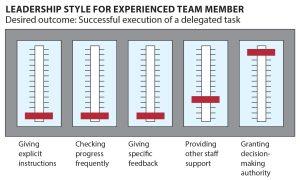

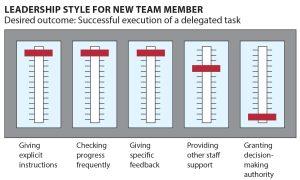

In planning that calibration, you can consider where a person is in terms of his skills, experience, self-confidence, and the risk involved if the task is not accomplished at a high level. Then you as the leader can decide what that means for your interactions with the team member — for example, whether you’ll need to provide more or less specific direction and feedback, engage in more or fewer frequent progress checks, and delegate more or less decision-making authority. This kind of calibration is especially valuable now, as staffing patterns and needs change rapidly and mounting student needs call for new supports and resources.

As an example of calibration, let’s say someone is leaving your team for a promotion after managing a complicated, important process for several years. The person to whom you’ll now be delegating this process has very little relevant experience, only a subset of the necessary skills, and shaky confidence in his own ability to accomplish this important task that must be executed extremely well.

Clearly, you will not be having the same conversations with this new person that you did in the most recent years with the former team member. The sound boards of your leadership style will look different for these two people. (See figures above and on p. 40.)

One of the key elements of this metaphor is that there are multiple factors to calibrate. Often, leaders think they have only two choices in their delegation style: either micromanage every aspect of the person’s work or leave the person alone.

Calibration is much more nuanced. And it starts with asking questions of yourself and the person you’ll be leading about the nature of the task, his or her current level of preparedness, and how the two of you will communicate along the way.

Building good question-asking habits

Asking purposeful, productive questions can become a habit. Like building any habit, it takes consistent effort over time. It’s up to you how to start, but for most of us, success is incremental rather than sudden.

I recommend starting with one aspect of questioning, such as one of the six I’ve described here, and practice it, giving yourself some time to get better at it until it starts to feel somewhat natural. Continue to practice until you don’t have to think about it. Then you’ll be ready to focus on another aspect.

Learning to ask good questions and truly listen to the answers is an ongoing process that challenges us to continually look inward to ourselves and outward to others. We are never finished with that growth, just as we are never finished developing relationships.

Over the years, I’ve often found that just when I think I’ve figured out what makes another person tick, an action or a response takes me by surprise and I’m reminded that I’m not a watchmaker. But I don’t have to be a watchmaker to keep asking good questions and letting the other person tell me what they think, what they need, and how I can help them become the best leader they can be for their colleagues and students.

References

Kouzes, J.M. & Posner, B. Z. (2006). The leadership challenge (Vol. 3). John Wiley & Sons.

Charles Mason (cmason.557@gmail.com) is retired superintendent of Mountain Brook City Schools in Alabama and a former president of the board of trustees at NSDC (now Learning Forward).

Comments are closed.